THE OTHER LESSON FROM THE SUPERMAN CHECK

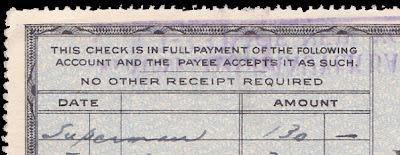

Everyone knows the story of how two Cleveland boys, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, created the character of Superman and, short of money, signed all their rights away to a corporation for $130. That corporation went on to reap hundreds of millions of dollars from their creation while Siegel and Shuster went hungry.

The infamous check which purchased the rights to Superman is now being auctioned. As of today the bidding stands at $36,000.

The check is one of those wonderful avatars that remind us how artists will always be prey to accountants on the food chain, and that the largest share of the profits will always go to those with the cunning to exploit someone else's creativity.

(It also reminds us why corporations should not have the legal rights of a natural person. In the words of Lord Chancellor Thurlow, a corporation is not a person because it "has no soul to be damned, and no body to be kicked.")

Lots of people (and also lots of lawyers) have spent years debating the lesson of the check for Superman. In long drawn out court battles and press campaigns, the corporations that prospered from Superman have been shamed or pestered into making supplemental payments and concessions to the families of Siegel and Shuster (who seemed to have the typical artist's penchant for mishandling their affairs).

But today I am interested in the other lesson of the check for Superman.

It is difficult to place a value on art because art has no inherent value aside from the value created by its context. A few years before selling the rights to Superman, the creators themselves placed little value on it; artist Joe Shuster burned pages of superman artwork because he couldn't find a single publisher willing to touch it. Then, a few years after buying the rights to Superman, the new owner had to sue those same publishers to keep them from infringing on the now valuable idea. What created the "value" in the art?

John Chipman Gray noted, "Dirt is only matter out of place," and the same point could be made about art. What is important and valuable art in one context may be worthless as dirt in another.

Much of the art we talk about here is art "out of place"-- it is located in ads for dish washing detergent, in faded magazines of fiction for housewives, or scratched on the wall of a hermit's basement apartment rather than hanging in a gold frame on a gallery wall. Art out of place-- unrecognized, misunderstood or unappreciated-- seems to have very little meaning or value.

Rather than being cause for despair, this should serve as a reminder to keep our eyes (and minds) open.

The next time two boys down the block tell you they have invented a really cool superhero, don't wait for some grandee of the art world to transport their creation into its "proper" place before you are capable of seeing it.