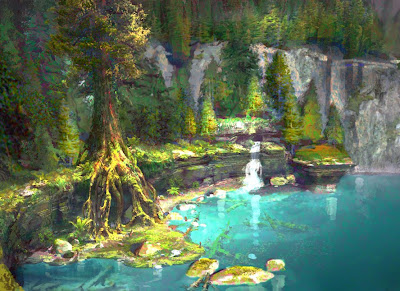

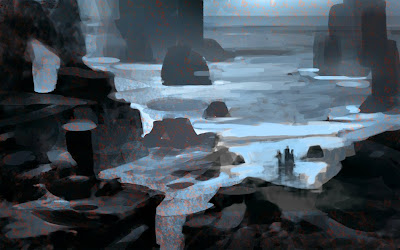

Shrek Forever After: mood roughs

. . Black prismacolor in a moleskine . At the very beginning of Shrek Forever After I had the opportunity to do lots of mood roughs for some spooky new locations. I was the only artist on the show and was experimenting so I had the leeway to do these in acrylic (the last acrylic painting I had done for animation was in 2000). Some of the roughs led to finished photoshop paintings (which I'll show in a later post) and you can see their influence in the ogre camp location in the finished cut of the show.