WHERE MEN AND MOUNTAINS MEET

William Blake, the great English mystic, observed:

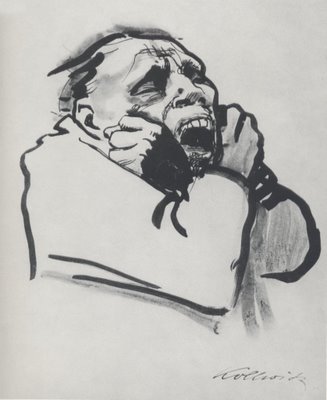

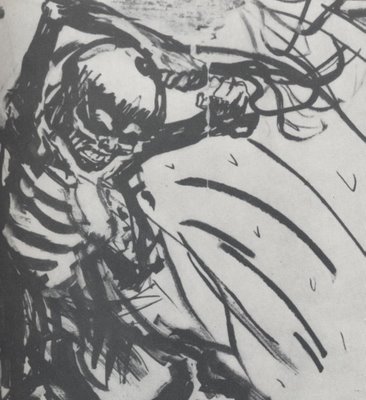

Kollwitz lived through two World Wars in Germany where she worked with her husband in the most impoverished areas of Berlin. Her artwork passionately depicted the plight of the poor and oppressed. As a mother and peace activist, she suffered the twin nightmares of losing her son in World War I and losing her grandson in World War II. Here is her mournful picture of a mother searching for her dead son on a battlefield:

Kollwitz was persecuted by Nazi goons who considered her pictures "degenerate art." Her career was blocked and her home was bombed but she refused to be intimidated into leaving Germany. She also refused to stop working, saying "Drawing is the only thing that makes my life bearable." She was one of the most powerful graphic artists of the 20th century.

The place "where men [or in this case, women] and mountains meet" is difficult terrain for an artist. Artists who choose to portray injustice or death (as opposed to flowers or landscapes) tend to get carried away and sacrifice form for content. They often become shrill, or stray from art into the realm of political propaganda.

William Butler Yeats, another cool poet, warned of the dangers of mixing propaganda and art:

I admire artists who take the big chances, as long as they retain artistic perspective equal to their passion. For me, that is a far better test than the one offered by Yeats for an artist who takes on big content: is she capable of creating artistic forms strong enough to contain that content?

Kollwitz passes that test. In my view, she puts to shame much of today's smug art establishment. By casting our eyes back to the place where a woman and mountains once met, we can gain some perspective on just how far we have relaxed our standards to accommodate today's minor artists "jostling in the street." Their tiresome fascination with their own neuroses and bodily functions seems trivial compared to the majestic example of Kaethe Kollwitz. .

Great things are done when men and mountains meet;That is why I have a special fondness in my heart for artists such as Kaethe Kollwitz (1867-1945) who were driven to grapple with the big subjects-- life and death, injustice, war and peace.

This is not done by jostling in the street.

Kollwitz lived through two World Wars in Germany where she worked with her husband in the most impoverished areas of Berlin. Her artwork passionately depicted the plight of the poor and oppressed. As a mother and peace activist, she suffered the twin nightmares of losing her son in World War I and losing her grandson in World War II. Here is her mournful picture of a mother searching for her dead son on a battlefield:

Kollwitz was persecuted by Nazi goons who considered her pictures "degenerate art." Her career was blocked and her home was bombed but she refused to be intimidated into leaving Germany. She also refused to stop working, saying "Drawing is the only thing that makes my life bearable." She was one of the most powerful graphic artists of the 20th century.

The place "where men [or in this case, women] and mountains meet" is difficult terrain for an artist. Artists who choose to portray injustice or death (as opposed to flowers or landscapes) tend to get carried away and sacrifice form for content. They often become shrill, or stray from art into the realm of political propaganda.

William Butler Yeats, another cool poet, warned of the dangers of mixing propaganda and art:

We make rhetoric out of arguments with others but we make poetry out of our arguments with ourselves.The pictures above may seem a little extreme, which is why the fine art establishment sometimes looked down on Kollwitz as a "propagandist." But look at the miraculous drawings below. This is not the work of an artist gone hoarse from yelling. This is the delicate touch of a first class artist with great sensitivity and insight.

I admire artists who take the big chances, as long as they retain artistic perspective equal to their passion. For me, that is a far better test than the one offered by Yeats for an artist who takes on big content: is she capable of creating artistic forms strong enough to contain that content?

Kollwitz passes that test. In my view, she puts to shame much of today's smug art establishment. By casting our eyes back to the place where a woman and mountains once met, we can gain some perspective on just how far we have relaxed our standards to accommodate today's minor artists "jostling in the street." Their tiresome fascination with their own neuroses and bodily functions seems trivial compared to the majestic example of Kaethe Kollwitz. .